| Whether

natural variability could be the reason for the existence of a ‘significant’

global warming trend – contributing to rising levels of greenhouse

gases in the atmosphere is highly contentious. These views are pushed

by those who still remain sceptical about the link between climate

change and human activity.

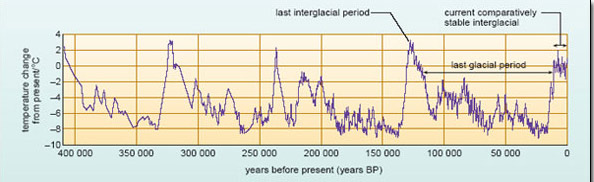

Temperature

changes over the past 400 000 years reconstructed from the Vostok

ice core, the longest continuous ice-core record to date. Introduction

to Climate Change, UNEP/GRID, Arendal, Norway; Figure 3.5 Kunsthistorisches,

Museum, Vienna/ Bridgeman Art Library;

This

record tells us, for example, that the Earth entered into the most

recent comparatively cold period of its history (known as the Pleistocene

Ice Age) around 2.6 million years ago. On a geological time-scale,

these Ice Ages are relatively rare, covering only 2–3% of

the history of our planet. The characteristic feature of the current

one (and there is no reason to suppose that it is finished) is evident

in the above graph. Drilled in Antarctica, the Vostok ice core provides

a temperature record that goes back several hundreds of thousands

of years. Beyond about 10 000 years ago, it tells a story of an

unstable climate oscillating between short warm interglacial periods

and longer cold glacial periods about every 100 000 years –

with global temperatures varying by as much as 5 to 8 °C –

interspersed by many more short-term fluctuations

By contrast, global temperatures over the

last 10 000 years or so seem to have been much less variable, fluctuating

by little more than one or two degrees. In short, the interglacial

period in which we live, known as the Holocene, appears (on available

evidence) to have provided the longest period of relatively stable

global climate for at least 400 000 years. It is almost certainly

no coincidence that this is also when many human societies developed

agriculture and when the beginnings of modern civilisations occurred.

We now shift the focus to the more recent past – the period

during which human population growth and the coming of the industrial

age began to make their mark on the composition of the atmosphere.

Contested

science: a case study

For complex issues such as global climate change, there

are many opportunities for scientists to take issue with

the findings of their colleagues. They can disagree about

the procedures for gathering data, the completeness or coverage

of the data, how the data are analysed and interpreted,

and then finally the conclusions. The assumptions that shape

a particular piece of research and inform the kind of questions

that will be asked can be no less contentious than the quality

of the data gathered.

Such contention is not unique to climate science, of course.

Fuelled in part by very human concerns such as a desire

to protect one's reputation, competition for funding, etc.,

vigorous debate is the lifeblood of science; it helps to

drive further investigation and innovation. In scientific

areas where society has pressing concerns, however, influences

beyond the normal cut and thrust of scientific debate come

into play. Scientists are typically aware of the potential

policy implications of their research, and may shape their

work accordingly. Often, such research is stimulated or

funded by organisations with an interest in the outcome

of the policy debate. In turn, interest groups and policy

makers tend to adopt a ‘pick n' mix’ approach

to the available scientific evidence, promoting research

that reinforces their existing arguments and beliefs, and

neglecting or criticising more uncomfortable findings. Equally,

the influence of individual scientists sometimes owes more

to their access to decision makers or the media than to

the reliability of their knowledge.

|

‘Global

Warming’. An OpenLearn chunk used/reworked by permission of

The Open University copyright © (2007).’ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/uk/

|

|