|

There

are seven species of sea turtle that have swum in the waters

of our planet since the time of the dinosaurs. These creatures

have successfully survived natural disasters, predators and

other threats for millions of years.

Now, human activity appears to be a problem they cannot surmount.

Multitudes of sea turtles are killed each year. Their shell

is used to manufacture expensive artifacts that can be sold

to tourists. Their meat is eaten as a luxury product, and

their blood and eggs are considered to have special medicinal

properties when consumed. Unfortunately, many communities

along the Mediterranean Sea, or other coastal areas frequented

by turtles, are involved in the illegal exploitation of turtles

either knowingly or unwittingly.

Historically indigenous peoples harvested sea turtles in small

numbers, however the versatility of turtles as a commodity

combined with their utter defenselessness has turned a sustainable

hunting practice into a destructive commercial enterprise

that has, combined with other threats, left all seven species

of sea turtle endangered. |

| A

turtle slaughtered for its meat on the beaches of Boavista Island

(Photo: Daniel Cejudo, Proyecto Cabo Verde Natura) |

Commercial

Uses of Sea Turtle Parts

Fatty tissues are processed to make oil and creams. These

tissues were historically used to produce oil for lamps, boat varnish,

and cosmetics. Currently vials of turtle oil are marketed as medicines

or for use as an aphrodisiac.

Blood: In some cultures sea turtle blood is used as a cure for anemia

and taken to promote fertility.

Eggs are sold as a delicacy and touted to promote longevity and

virility

Shells of Hawksbill turtles are used as material for various artifacts.

Whole shells are varnished and sold as decoration or individual

scales can be molded into jewelry, or used as decoration on any

number of objects

Meat from turtles is traditionally eaten in many cultures or served

as a delicacy to tourists.

| Threats

to Green Turtles |

|

|

The

Green Turtle has been subject to exploitation since the 1600s

when British colonists first arrived Jamaica and Bermuda. Turtle

meat was imported from the Cayman Islands and soon became a

staple food. On long sea voyages turtles also provided a continuous

supply of fresh meat, as they were easy to keep alive on board

until they were needed for sustenance.

Laws preventing the exploitation have been recorded as early

as 1620 when settlers first began to notice the significant

decline in Green Turtle populations. These laws proved to be

unenforceable however, and by the 20th century there was high

demand internationally for nearly every part of the Green Turtle’s

body and shell. |

Across

the world, Green Turtle eggs and meat are considered a gourmet

food, the shells can be carved into ornaments and jewelry,

and the skin is tanned into leather. In some markets one can

even find entire baby turtles that have been stuffed and sold

as keepsakes.

Historic

records show that at the beginning of the 20th century it

was normal to catch Green Turtles weighing nearly 1,000 pounds,

however the continual exploitation of these turtles has literally

caused them to shrink. Today, a 300-pound Green Turtle would

be considered abnormally large.

Although

the Green Turtle is internationally recognized as a threatened

species certain countries still allow the slaughter or importation

of Green Turtle products for economic or cultural reasons.

Other places lack the resources to effectively enforce turtle

protection legislation. For these reasons, a large black market

for Green Turtle products still exists worldwide which draws

in local participation with the promise of a significantly

higher income than that which could be earned simply by fishing

or other endevors.

|

| Threats

to Hawksbill Turtles Hawksbill

Turtles are most famous for their beautiful shells, which

are turned into jewelry, eyeglass frames and other trinkets.

Entire turtles have also been found stuffed and sold as wall

hangings. Although steps have been taken to prevent the international

trafficking of Hawksbill shells, a large underground market

still exists and some countries, most notably Japan, still

openly permit the sale of Hawksbill shell artifacts.

|

|

| Threats

to Olive Ridley Turtles Olive

Ridley Turtles find themselves particularly at risk due to

their nesting practices. While most other turtles nest individually,

Olive Ridleys take part in mass nesting where thousands of

females congregate on the same beach on a certain night. As

a result, they become easy targets for poachers, who can collect

many turtles and eggs in the same night.

|

A

Hawksbill Turtle is butchered in the Gulf of Venezuela (Photo:

Hector Barrios-Garrido. Grupo de Trabajo en Tortugas Marinas

del Golfo de Venezuela) |

One

man was particularly infamous for his role in the exploitation

of Olive Ridleys in Mexico. Antonio Suarez ran a number of

plants that processed Olive Ridleys for international sale.

In 1978 alone, one of these plants processed over 50,000 Ridleys,

90% of which had been collected during nesting. In 1980, Suarez

was involved in a failed attempt to smuggle roughly 106,000

pounds of Olive Ridley meat into the US, which was estimated

to have come from 8,800 turtles.

Despite his indictment for smuggling, Suarez still owned and

operated 3 slaughterhouses as late as 1990.

Suarez’s and other similar large-scale operations had

a devastating effect on the Olive Ridley population that may

prove to be irreversible. Today, there is still a significant

amount of black market activity involving Olive Ridley Turtles,

although large-scale slaughtering operations have been largely

shut down. |

|

| |

A

dead Olive Ridley cut open for eggs on the Pacific Coast of

Guatemala (Photo: Rachel Brittain) |

| Threats

to Kemp Ridley Turtles

Although at one time Kemp

Ridley Turtles were common throughout the Caribbean, by the

1940s, nesting activity was only seen on one beach in northeastern

Mexico. Even then, one mast nesting on this beach was estimated

to have included 40,000 female turtles. Several years later,

after the continued unchecked harvesting of females during

nesting, only 500 nests were recorded. Research shows that

in recent years the Kemp Ridley population has begun to increase

again, but existing Kemp Ridleys are still vulnerable to the

types of exploitation that affect all sea turtles.

|

|

| |

A rare Kemp Ridley nesting at Padre Island

(Photo: Cynthia Rubio) |

|

Threats

to Loggerhead Turtles

Despite significant efforts

to conserve Loggerhead Turtle populations worldwide these

turtles are especially vulnerable to the destructive impacts

of fishing as well as black market activities. Due to their

unwieldy size, it is easy for them to become entangled in

drift nets and long fishing lines, which can wrap tightly

enough to injure or kill the turtle. Loggerhead nesting

beaches in the Mediterranean are particularly vulnerable

to development for tourism, which discourages the females

from leaving the water to nest. Loggerhead shells are also

particularly coveted for their ornamental value.

|

| Loggerhead

carapaces put out for sale in Mdiq Market, Morocco (Photo: Wafae

Benhardouze and Mustapha Aksissou) |

|

| Threats

to the Flat Back Turtle

Perhaps because their meat is considered distasteful,

the Flat Back Turtle appears to be less at risk than other

sea turtle species. Conservation efforts in Australia and

the surrounding islands (the only region where the Flat Back

is commonly found) have helped to protect nesting areas from

poaching activity although the harvesting of eggs has yet

to be eliminated.

|

|

| |

A

Flat Back Turtle sighted early one morning on Barrow Island

(Photo: Jarrad Sherborne) |

|

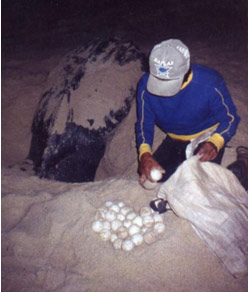

The

Leatherback Turtle, as the largest living species of sea turtle

is particularly valued for its meat and eggs. Egg harvesting

has been particularly problematic and has caused a significant

decline in population. Drift nets also pose a sever threat

to Leatherbacks as they are unable to escape drowning in them

once they become trapped. |

| A poacher

in Oaxaca, Mexico takes eggs from a nesting Leatherback. (Photo:

Alejandro Fallabrino) |

|

Links

- www.cites.org

- http://www.sos-seaturtles.ch

In English and French

- http://www.cccturtle.org/cites.php

Sources:

- http://www.endangeredspecieshandbook.org/trade_reptile_seaturtles.php

- www.cat.inist.fr ? Muséum

National d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris / Congrès sur

le commerce et l’exploitation des animaux sauvages. Only in

French.

- www.c-3.org.uk

- www.fieldstudies.org

- www.frinos.com

Acknowledgement to Samantha Nier for her help with this webpage.

|

|